Nation Of Language On How “Idioteque,” Anne Carson, La Chimera, & More Influenced New Album Dance Called Memory

Back when Nation Of Language were releasing their 2020 debut album Introduction, Presence, frontman and songwriter Ian Devaney said he hoped the band’s music would create “a space in which to ache.” Since first naming them a Band To Watch in 2018, we witnessed NOL ascend from a local NYC act to, just recently, stepping onto arena stages opening for Death Cab For Cutie. Dance Called Memory — their Sub Pop debut, out this Friday — is their fourth album in five years. And as their stature has risen with each release, the space in which to ache has only grown larger.

For Dance Called Memory, the trio — Devaney, his wife and right-hand synth wizard Aidan Noell, and bassist Alex MacKay — once more teamed with LCD Soundsystem/Holy Ghost! member Nick Millhiser as producer. Together, the crew pushed the edges of NOL’s sound, creating something expansive enough to capture the weight of grief and loss that coursed through these new songs. There are the customary synth-pop jams — “In Another Life,” “Inept Apollo,” “In Your Head” — but now they sit along blooming, atmospheric tracks like “Can’t Face Another One” or “Under The Water.” Notably, Devaney found solace in his original instrument, the guitar, leading to both the Cocteau Twins washes of “I’m Not Ready For The Change” and the pensive beauty of spare tracks like “Can You Reach Me?” and “Nights Of Weight.”

Devaney’s moods in these songs are familiar: listless, searching, melancholic. But on Dance Called Memory, he renders them with a more weathered maturity accrued across four albums and countless miles traveled. Now in his mid-thirties, Devaney spends the album reckoning not just with the people and things that fade away or exit our lives entirely, but how to make sense of a mind tangled with memories, the realization of how much more crowded our rearview mirror becomes as we age.

Accordingly, Devaney drew inspiration from a host of sources while working on Dance Called Memory, movies and poems that clarified the ennui and existentialism he experienced. He looked to musical references both new and core to his identity as a person, but ones that encouraged new textures in Nation Of Language’s music. Read our conversation below.

La Chimera (2023)

IAN DEVANEY: Anytime I watch a movie and it makes me want to make art, I think it’s a very powerful thing. This movie, more than any other movie in the past few years, did that. It has this guy who can supposedly detect where graves are using a divining rod, but it’s chronicling him dealing with the grief of losing his wife. There’s a beauty in how it’s presented. He’s surrounded by death and he’s struggling with it all the time because his job is to rob graves.

There’s also something about his presentation. It made me think of Paris, Texas as well. You have this protagonist who’s in this trashed suit throughout much of the movie, and it speaks to this former put-togetherness that’s been dragged through the mud. That was a compelling visual to me. After I saw it I was like, “I want to get a suit and I want to wear the hell out of it,” because it makes me feel as if I’m expressing myself through my clothes.

It does deal in a lot of the same subjects as the album, and does so in a medium I don’t know how to work in. They did it in a way that spoke to me so much. It made me want to tell everyone I knew about that movie.

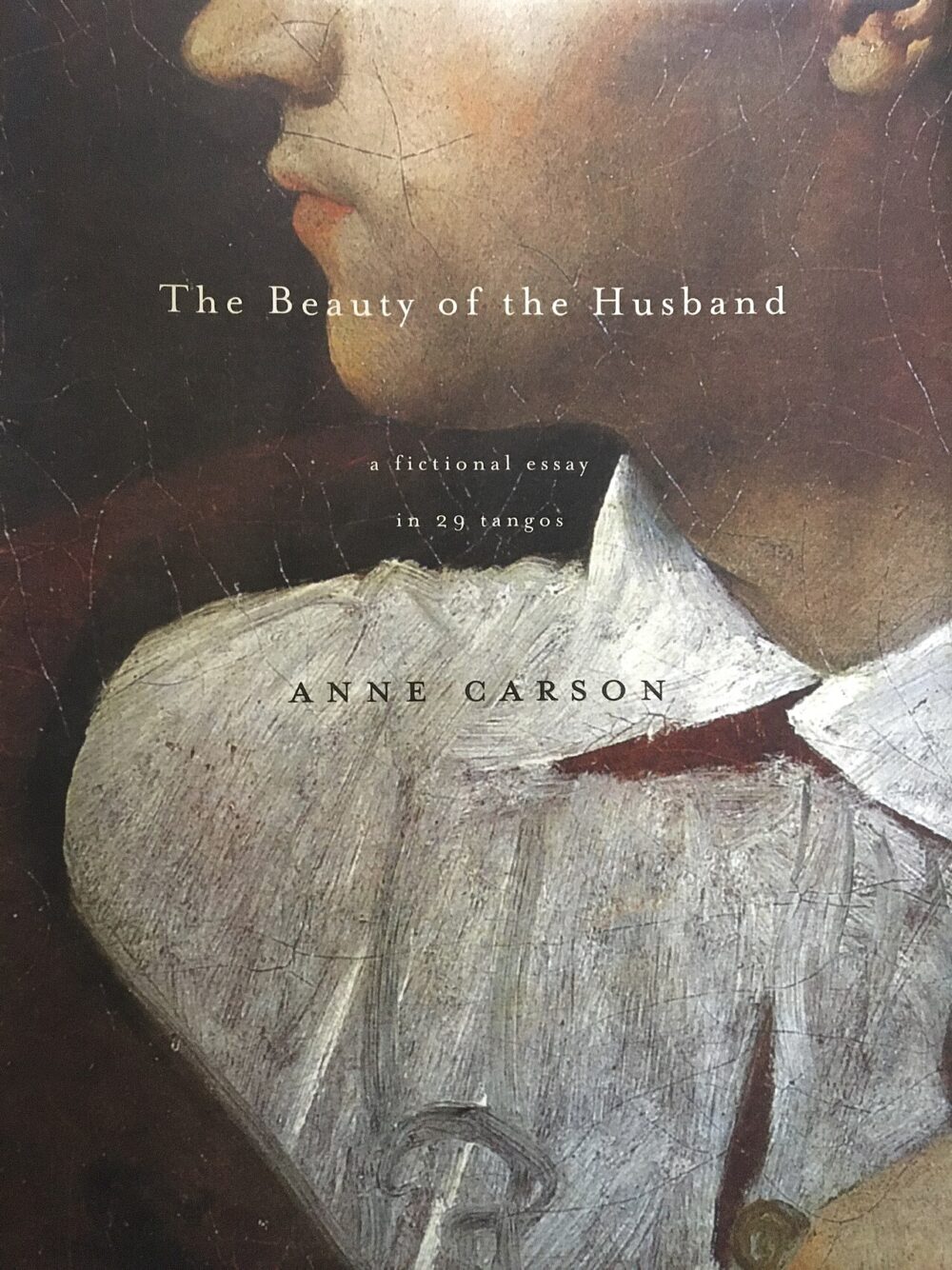

Anne Carson’s The Beauty Of The Husband (2001)

DEVANEY: The Beauty Of The Husband is a poetry book that chronicles a marriage. It’s broken into these 29 short chapters of verse, and each one begins with a standalone thought of sorts. There’s one that’s talking about memory and says: “Do you see it as a room or a sponge or a careless sleeve wiping out half the blackboard by mistake or a burgundy mark stamped on the bottles of our minds what is the nature of the dance called memory.”

Aidan had read this book first and underlined that a bunch. When we were trying to come up with the album title, I was poring through the lyrics, but everything felt either too specific to the song it was in. She handed this to me. I glanced at it and put it down, but every two minutes I found myself looking back over. The more I did, the more it wouldn’t leave my mind.

There’s something very dancelike, very fluid, about our memories and how we engage with them. At times we want to pull them close, at times we want to keep them distant. Everything feels like it’s sort of swirling and shifting as you move through life. That phrase summed up so much of the record.

You and I are the same age, and I feel like the first half of your thirties can be spent reckoning with what you want to carry with you or not from the first stages of adulthood. In the album bio, you referenced coming across this photo of a party. There were couples no longer together, friends who were no longer friends. There’s always been melancholy and yearning and memory across Nation Of Language albums, but has this hit some different critical mass as you’ve gotten to your mid-thirties?

DEVANEY: I wonder if this is a false notion or something that is true and will only get truer: that the things that happen to you as you get older have a greater weight to them, perhaps because you’re closer to death. As far as relationships go, there’s something interesting that happens in your thirties. People are deciding about marriage and kids and these big questions of life for which there seems to be some kind of timer. I do think there’s this added thing if friendships or relationships made it through your twenties, you hope or think we all would’ve figured enough out to make things work. And sometimes they just don’t. Something about all of that happening with age feels extra heavy.

I always try to remind myself now that in the same way that all these things can break apart in just a few years, that the new reality in which you find yourself does not have to be the final reality. There are people I didn’t get along with in my early twenties, and if I ran into them now I’d consider it a fresh start. We’re all in such different circumstances and have changed so much. While life is in some ways a string of losing things, there are also constant opportunities for renewal. That’s something that’s not exactly reflected in the lyrics of the album. [Laughs] But it’s something I try to believe anyway.

Mojave 3’s Ask Me Tomorrow (1995)

DEVANEY: I didn’t even know it existed until a few years ago. They execute this lonesome West eternal expanse thing really well. That was a visual that was on my mind for a lot of these songs, particularly “Can’t Face Another One,” the first song on the album. It starts with harmonica to bring you into that world. A person walking through a wasteland, maybe simultaneously running from something and searching for something.

You once told me that if the first album took place in an automobile, and the second on trains, then the third was walking various city streets.

DEVANEY: I forgot about this micro-narrative. I guess this one might be “trudging through the desert.” For me, the desert is a very evocative place for the fact it’s inhospitable and can seem endless. But on a personal level being a touring musician: When you find you’re out West and you’re in those conditions that’s when you know you have really left home behind. To some degree, it speaks to the idea you just have to keep driving forward.

In the song “Inept Apollo,” there’s this notion of having impostor syndrome about the one tool you have to escape your sadness. All I have is going on tour and putting on this show and freaking out onstage and hoping people like it. It gives you a sense of agency about your life, and it makes you feel like you’re leaving a lot of life behind. Putting it in the rearview. Falsely escaping, even though you know you’ll be coming right back to it. Anything out west has a real magical essence in my mind, because it means you’re truly out there.

The Pretenders’ Acoustic “Back On The Chain Gang” From The Isle Of View (1995)

DEVANEY: This became an accidental influence. I was learning that song because I covered it at one of our shows, just me and a guitar. It very much speaks to the existential feelings I was having. I had strung my guitar into what’s called “Nashville tuning,” and it really makes chords chime differently. I found I was just constantly picking up the guitar. It was feeling so good in my hands, and playing it was such a good distraction from being terribly sad. In the course of playing guitar so much, several songs were cooked up — “Can You Reach Me?” and “Nights Of Weight” especially. “Back On The Chain Gang” ended up looming very large. It’s a song I liked, but it became a conduit for putting the guitar back in my hands a lot.

Radiohead’s “Idioteque” (2000) And The DFAM Synth

DEVANEY: We were trying to introduce instruments we’re not that familiar with this time. Nick and I made Strange Disciple and half of A Way Forward together. You don’t want things to feel too stale. There’s this Moog synth called DFAM, Drummer From Another Mother, which became important for songs like “In Another Life” and “Inept Apollo.” The way that synth works lends itself to that “pew pew pew” sound. It’s a percussion synthesizer, which is different than a drum machine. You’re making up these sounds and changing them as the beat is developing. That was very different for me, and sparked a lot of excitement and improvisation.

The DFAM felt like a way for me to access a palette that felt sort of similar to “Idioteque,” one I felt I’d never had access to. “Idioteque” was the first Radiohead song I knew. My dad took me to see them on August 18, 2003. I remember just waiting for them to hit “Idioteque.” While Dance Called Memory might be very heavy and morose, we didn’t want it to be drudgery to listen to. We wanted it to be fun, engaging. I think Kid A is an example of an album that does that very well.

Louise Gluck’s “October” (2004)

DEVANEY: I got this massive compendium of her work. I found whatever page I turned to, she was able to speak about grief or loneliness or struggling with bitterness in really amazing ways. In the poem “October,” there’s this one particular line I kept thinking of as I was making the record:

Tell me this is the future,

I won’t believe you.

Tell me I’m living,

I won’t believe you.

I think the shock of loss can leave you in disbelief at the state of things. The way my brain works is I’m always looking for a plan and a path onward. When you’re blindsided by something, or several things at the same time, it puts you on your heels. You have no idea what to do next. You have no idea how to chart a path through it. This was the first poem of hers I knew, and I feel as if the themes really resonated with those on the album.

The Beatles Get Back Documentary (2021)

DEVANEY: For me this was just a great view into the diligence of songwriting. There are times when it just comes to you and falls from the sky and it’s like “Oh, fantastic!” And there are times when you have to play “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” 500 times and throw random words into random places and see how it pans out.

There’s a moment when Paul McCartney says one of the proposed lyrics sounds good but doesn’t sing well. There are so many times when you come up with an idea and the way you want to put the words together butts up against the space of the song, or how the vowels or consonants would fit together. As a songwriter, that was very illuminating. He put into words a concept I’d struggled with for a long time. You do want things to “sing well.” You can think of examples when you’re singing along to something and someone has forced words in. It can feel clumsy. This documentary was just inspiring about applying yourself to your craft, but it also influenced our video for “I’m Not Ready For The Change.”

Cocteau Twins, My Bloody Valentine, And The Transition From The ’80s To The ‘90s

Connecting this back to Mojave 3 and the Pretenders, I was thinking about the pivot some bands make — like Slowdive and all their alien sounds transitioning to Mojave 3 and something more organic. Many of the great synth bands at some point did this, too. Guitar has been creeping into NOL’s music more and more, but does so in more profound ways on Dance Called Memory.

DEVANEY: This and Mojave 3 do also connect with My Bloody Valentine, Cocteau Twins, and the ’80s turning into the ’90s. This smashing of eras and technologies and there being this strange overlap. I think, for us, it shows up both in the prevalence of guitars but also in something like the breakbeats of “I’m Not Ready For The Change.” The rhythm of that song is very much inspired by “Soon” by My Bloody Valentine. Capturing this blend of the space alien noises and the real noises.

You and I were both born in 1990. I think of the late ’80s and early ’90s as a weird musical time, a kind of awkward middle ground with a lot of growing pains sounds. Were you looking back to this time as a way of recalling childhood, or was it more like observing these evolutions while Nation Of Language is in some kind of metamorphosis phase?

DEVANEY: While that is true, they weren’t the sounds I was surrounded by. My parents weren’t particularly into My Bloody Valentine or any of that. People were being ambitious with tools that felt sort of clumsy. You had had analog synths into digital synths and then into big guitar effects with shoegaze. To me, that makes a lot of sense with synthesizers. It’s a very logical pairing. I think it’s interesting to view a perhaps clumsy time from afar and be like, “Oh, these parts of it were really sick.” Some things from that era might sound dated and cheesy. But I think of synths and recording technology and gear from that era, it was all in this early digital stuff that didn’t stick around. Older analog gear can be more easily repaired and used again, where a lot of the stuff from that era is probably in the trash heap somewhere.

When this was happening, the culture was going away from new wave and into this other thing. My mind says, why does it have to be an either/or. Combining these things makes sense to me. It seems one grew out of the other in some ways. It’s nice to feel like you can expand what the band does.

I don’t think it’s an indication of direction, like Nation Of Language will sound like something different from here on out. But being able to have the breakbeats on “I’m Not Ready For The Change” or a strummed guitar and no drums on “Nights Of Weight” — it feels scary. I’m sure there are fans of ours where the closer we point to new wave, the better for them. You hope the underlying songwriting is actually what brought people in, and if you redid any of these as country songs, they would still like it. Exploration and the expansion of the textural palette is scary, but it’s the exciting kind of scary.

Dance Called Memory is out 9/19 on Sub Pop.